History of Mali

| History of Mali |

|---|

|

| Ghana Empire (c. 700 – c. 1200) |

| Gao Empire (9th century–1430) |

| Mali Empire (c. 1235–1670) |

| Songhai Empire (1464–1591) |

| Post-Imperial, 1591–1892 |

| French colonization |

| After Independence |

| Related topics |

|

|

Mali is located in West Africa. The history of the territory corresponding to modern-day Mali can be divided into several periods:

- Pre-Imperial Mali, before the 13th century

- The era of the Mali Empire and later the Songhai Empire, from the 13th to the 16th centuries

The present borders of Mali correspond to those of French Sudan, established in 1891. These boundaries are colonial and artificial, grouping together regions from both the Sudan and Saharan zones. As a result, Mali is a multiethnic country, with the Mandé peoples forming a significant portion of the population.

Mali's history is deeply shaped by its strategic role in Trans-Saharan trade, connecting West Africa with the Maghreb. The city of Timbuktu is emblematic of this legacy: located on the southern edge of the Sahara near the Niger River, it became a major hub of commerce, scholarship, and culture from the 13th century onward. This growth was particularly pronounced during the rise of the Mali Empire, followed by the expansion of the Songhai Empire, which emerged as a dominant power in West Africa.

Prehistory

[edit]Paleolithic

[edit]The Sahara has experienced significant climatic fluctuations throughout its history, with periods both drier and wetter than today. As a result, it was inhospitable to human life during certain intervals, such as between 325,000–290,000 years ago and again between 280,000–225,000 years ago, except for a few favorable refuges like Lake Tihodaïne in the water-retaining Tassili n'Ajjer region[1].During these arid phases, the desert expanded far beyond its present-day boundaries, leaving behind sand dunes that stretch well beyond the modern Sahara. Human occupation is primarily linked to the wetter "green" phases, when ecological conditions were more suitable for settlement and migration.

It is possible that anatomically modern humans, who may have emerged in isolation south of the Sahara between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago, already inhabited the humid, water-rich regions during a prolonged green phase over 200,000 years ago. Around 125,000 to 110,000 years ago, an extensive network of rivers and lakes enabled the northward spread of fauna, followed by human hunter-gatherer groups. Among these water systems was Mega Lake Chad, which at its largest extent covered over 360,000 km²[2]. However, during a subsequent arid phase between 70,000 and 58,000 years ago, the Sahara once again became a formidable barrier to migration. Another green period followed between 50,000 and 45,000 years ago[3].

In present-day Mali, archaeological evidence is less abundant than in northern neighboring regions. However, excavations at the Ounjougou complex[4] on the Dogon Plateau, near Bandiagara, have revealed signs of human presence dating back over 150,000 years. Evidence of continuous habitation is firmly established for the period between 70,000 and 25,000 years ago. The Paleolithic period in Mali ended relatively early, likely due to the onset of another extremely arid phase — the Ogolia — around 25,000 to 20,000 years ago, which transformed the region back into a dry savannah landscape[5].

Neolithic

[edit]This section may require copy editing. (March 2025) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2025) |

Following the last glacial maximum and the retreat of northern ice sheets, the climate in the Sahara region became significantly more humid than today. The Niger River formed a vast inland lake near Timbuktu and Araouane, while a similarly large body of water developed in the Lake Chad basin. During this period, which began around 9500 BCE, the landscape of northern Mali resembled the savannah ecosystems found in southern Mali today. The humid phase that followed the Younger Dryas (a cold climatic episode) was eventually replaced by increasing aridity around 5000 BCE.

The Neolithic period, marked by a transition from foraging to food production, developed during this wetter era. It is usually divided into three phases, separated by distinct dry intervals. Sorghum and millet were among the earliest cultivated crops, and by 8000 BCE, large herds of cattle—closely related to modern zebus—grazed across what is now the Sahara. Sheep and goats were introduced much later from West Asia, whereas cattle were likely first domesticated within Africa.

Pottery appeared independently at several sites, including Ounjougou in central Mali, with ceramics dated to around 9400 BCE—one of the earliest known examples in West Africa[1]. Some of the earliest Neolithic cultures practiced a productive way of life without fully developed agriculture or animal husbandry. At the Ravin de la Mouche site (part of the Ounjougou complex), dates between 11,400 and 10,200 years ago have been recorded. Other nearby sites, such as Ravin du Hibou 2, date to between 8000 and 7000 BCE. However, a hiatus in occupation is evident between 7000 and 3500 BCE, likely due to unfavorable climatic conditions that even hunter-gatherers could not withstand.

Archaeological and paleoenvironmental data suggest a return of nomadic pastoralists around 4000 BCE, just prior to the end of the last humid phase, which waned around 3500 BCE. Sites like Karkarichinkat (ca. 2500–1600 BCE) and possibly Village de la Frontière (ca. 3590 cal BCE), along with sediment layers at Lake Fati, illustrate this period of climatic transition. Lake Fati existed between 10,430 and 4660 BP, with a 16-centimeter sand layer indicating a desiccation event around 4500 BP—approximately 1,000 years later than comparable changes on the Mauritanian coast. Increasing aridity peaked about a millennium later, prompting southward migrations of cattle-herding populations into Mali as northern lakes dried up[2].

This late Neolithic period also saw further immigration from the Sahara around 2500 BCE, as the region transitioned into an increasingly arid desert. Archaeological surveys based on ceramic typology identified three cultural groups living around Méma, the Canal de Sonni Ali, and Windé Koroji (near the Mauritanian border) around 2000 BCE. Key excavation sites include Kobadi (1700–1400 BCE), MN25 (near Hassi el Abiod), and Kirkissoy near Niamey, Niger (1500–1000 BCE). These suggest a southward movement of populations, culminating in the introduction of agriculture, including the cultivation of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) and possibly wheat and emmer—grains domesticated much earlier in eastern Sahara, now reaching Mali. Ecological evidence implies tillage began as early as the 3rd millennium BCE, though this phase ended abruptly around 400 BCE due to severe drought.

The use of ochre in funerary practices—sometimes extending to animals—persisted into the 1st millennium BCE. A striking example is the burial of a horse at Tel Matamata, west of the Inland Niger Delta near Thial in the Tenenkou Cercle, where the remains were covered with ochre. Rock art, including both symbolic and anthropomorphic depictions, is found across Mali in areas such as Boucle du Baoulé National Park (Fanfannyégèné), the Dogon Plateau, and along the Niger River Delta (Aire Soroba).

Further excavations at Karkarichinkat Nord (KN05) and Karkarichinkat Sud (KS05)—located in a fossil riverbed roughly 70 km north of Gao—revealed the earliest known evidence in West Africa south of the Sahara for ritual tooth modification among women, dating to ca. 4500–4200 BP. These practices, which included tooth filing and extractions resulting in pointed teeth, resemble similar customs documented in the Maghreb. The modification was predominantly observed in female remains, and similar traditions continued in the region into the 19th century[3].

Isotopic analysis from these sites showed that 85% of dietary carbon came from C4 plants, particularly grasses, indicating either the consumption of wild cereals (like wild millet) or early domesticated species[5]. These results offer some of the earliest evidence of agriculture and cattle herding in West Africa, around 2200 cal BP.

The Dhar Tichitt tradition (1800–800/400 BCE), centered in the Méma region—a former river delta west of today’s Inland Niger Delta (sometimes called the “dead delta”)—represents another major cultural development. Settlements ranged from 1 to 8 hectares but were not continuously occupied, likely due to environmental limitations. The tsetse fly, prevalent during the rainy season, posed a significant obstacle to cattle rearing and limited expansion to the south.

By contrast, the Kobadi tradition, which developed in the mid-2nd millennium BCE, relied primarily on fishing, gathering wild grasses, and hunting, and remained relatively sedentary. Both traditions utilized copper sourced from Mauritania and maintained interregional exchanges, as evidenced by material culture and stylistic similarities in ceramics.

Earlier Iron Age

[edit]A number of early towns and cities were established by Mandé-speaking peoples related to the Soninke, along the middle Niger River in what is now Mali. Among the earliest was Dia, which is believed to have been settled around 900 BCE and reached its peak around 600 BCE[6]. Another major site was Djenné-Djenno, occupied from approximately 250 BCE to 800 CE[7]. Djenné-Djenno formed a substantial urban complex, consisting of 40 mounds spread across a 4-kilometer radius[8].The site itself likely extended over 33 hectares (82 acres) and participated in both local and long-distance trade networks[9].

During Djenné-Djenno's second phase—which occurred during the first millennium CE—the site expanded significantly, possibly covering over 100,000 square meters. This period also saw the emergence of permanent mud-brick architecture, including the construction of a city wall. The wall, built using cylindrical mud-brick technology, was approximately 3.7 meters wide at its base and extended for nearly two kilometers around the town[9][10].

References to Mali appear sporadically in early Islamic literature. The 11th-century geographer al-Bakri (writing in 1068 CE) mentions the regions of "Pene" and "Malal," which may correspond to areas within early Mali[11].The historian Ibn Khaldun, writing in the late 14th century, recounts the conversion to Islam of an early Malian ruler known as Barmandana[12].Additional geographical details are found in the 12th-century works of al-Idrisi[13].

Empires

[edit]Ghana Empire

[edit]After Soumaoro Kanté's defeat in the Battle of Kirina in 1235, the Ghana Empire became permanent allies with the Mali Empire, later gradually submitting to their increasing dominance to become a submissive state.[14]

Mali Empire

[edit]The Mali Empire started in 1230 and was the largest empire in West Africa and profoundly influenced the culture of West Africa through the spread of its language, laws, and customs.[15] Until the 19th century, Timbuktu remained important as an outpost at the southwestern fringe of the Muslim world and a hub of the trans-Saharan slave trade. Mandinka from 13th to the 17th century. The empire was founded by Sundiata Keita and became known for the wealth of its rulers, especially Mansa Musa I. The Mali Empire had many profound cultural influences on West Africa, allowing the spread of its language, laws, and customs along the Niger River.[citation needed] It extended over a large area and consisted of numerous vassal kingdoms and provinces.[16]

The empire was known for its abundant gold resources, which were used to finance the construction of impressive architecture, such as the famous Great Mosque of Djenné. The Mali Empire was also known for its thriving trade network, which stretched across the Sahara Desert and into North Africa and the Middle East.

The modern countries included are Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Mauritania, and parts of Niger and Burkina Faso. But Mali itself is the centre of the empire.

Songhai Empire

[edit]In the fifteenth century, with the Mali Empire weakening, Songhai, led by Sunni Ali Ber asserted their independence. The Songhai made Gao their capital and began an imperial expansion across the Niger valley, west to Senegal and east to Agades. At this time Songhai also seized control of Timbuktu.[17]

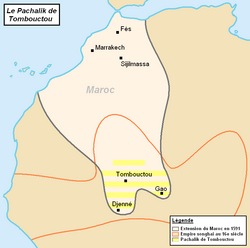

After the empires (1591–1892)

[edit]The Songhai empire eventually collapsed under pressure from the Moroccan Saadi dynasty. The turning point was the Battle of Tondibi of 13 March 1591. Morocco subsequently controlled Gao, Timbuktu, Djenné (also seen as Jenne), and related trade routes with much difficulty until around the end of the 17th century.

After the collapse of the Songhai Empire, no single state controlled the region. The Moroccans only succeeded in occupying a few portions of the country, and even in those locations where they did attempt to rule, their hold was weak and challenged by rivals. Several small successor kingdoms arose. The most notable in what is now Mali were:

Bambara Empire or the Kingdom of Segou

[edit]

The Bambara Empire existed as a centralized state from 1712 to 1861, was based at Ségou and also Timbuktu (also seen as Segu), and ruled parts of central and southern Mali. It existed until El Hadj Umar Tall, a Toucouleur conqueror swept across West Africa from Futa Tooro. Umar Tall's mujahideen readily defeated the Bambara, seizing Ségou itself on March 10, 1861, and declaring an end to the empire.

Kingdom of Kaarta

[edit]A split in the Coulibaly dynasty in Ségou led to the establishment of a second Bambara state, the kingdom of Kaarta, in what is now western Mali, in 1753. It was defeated in 1854 by Umar Tall, leader of Toucouleur Empire, before his war with Ségou.

Kenedougou Kingdom

[edit]The Senufo Kenedugu Kingdom originated in the 17th century in the area around what is now the border of Mali and Burkina Faso. In 1876 the capital was moved to Sikasso. It resisted the effort of Samori Ture, leader of Wassoulou Empire, in 1887, to conquer it, and was one of the last kingdoms in the area to fall to the French in 1898.

Maasina

[edit]An Islamic-inspired uprising in the largely Fula Inner Niger Delta region against rule by Ségou in 1818 led to the establishment of a separate state. It later allied with Bambara Empire against Umar Tall's Toucouleur Empire and was also defeated by it in 1862.

Toucouleur Empire

[edit]This empire, founded by El Hadj Umar Tall of the Toucouleur peoples, beginning in 1864, ruled eventually most of what is now Mali until the French conquest of the region in 1890. This was in some ways a turbulent period, with ongoing resistance in Messina and increasing pressure from the French.

Wassoulou Empire

[edit]The Wassoulou or Wassulu Empire was a short-lived (1878–1898) empire, led by Samori Ture in the predominantly Malinké area of what is now upper Guinea and southwestern Mali (Wassoulou). It later moved to Ivory Coast before being conquered by the French.

French Sudan (1892–1960)

[edit]Mali fell under French colonial rule in 1892.[18] By 1893, the French appointed a civilian governor of the territory they called Soudan Français (French Sudan), but active resistance to French rule continued.[16] By 1905, most of the area was under firm French control.[16]

French Sudan was administered as part of the Federation of French West Africa and supplied labor to France's colonies on the coast of West Africa.[16] In 1958 the renamed Sudanese Republic obtained complete internal autonomy and joined the French Community.[16] In early 1959, the Sudanese Republic and Senegal formed the Federation of Mali.[16] On 31 March 1960 France agreed to the Federation of Mali becoming fully independent.[19] On 20 June 1960 the Federation of Mali became an independent country and Modibo Keïta became its first President.

Independence (1960–present)

[edit]Republic of Mali République du Mali (French) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1968 | |||||||||||

| Motto: "Un peuple, un but, une foi" (French) "One people, one goal, one faith" | |||||||||||

| Anthem: "Le Mali" (French) | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Bamako | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary one-party socialist republic | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1960–1968 | Modibo Keita | ||||||||||

| Prime minister | |||||||||||

• 1960–1965 | Modibo Keita | ||||||||||

• 1965–1968 | Post abolished | ||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Decolonisation of Africa, Cold War | ||||||||||

• Independence from France | 20 June 1960 | ||||||||||

• Established one-party state | 1960 | ||||||||||

| 1962-1964 | |||||||||||

| 19 November 1968 | |||||||||||

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ML | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of Mali | ||||||||||

Following the withdrawal of Senegal from the federation in August 1960, the former Sudanese Republic became the Republic of Mali on 22 September 1960, with Modibo Keïta as president.[16]

President Modibo Keïta, whose Sudanese Union-African Democratic Rally (US/RDA) party had dominated pre-independence politics (as a member of the African Democratic Rally), moved quickly to declare a single-party state and to pursue a socialist policy based on extensive nationalization.[16][20] Keïta withdrew from the French Community and also had close ties to the Eastern bloc.[16] A continuously deteriorating economy led to a decision to rejoin the Franc Zone in 1967 and modify some of the economic excesses.[16][20]

In 1962-64 there was the Tuareg insurgency in northern Mali.

Under Moussa Traoré

[edit]Republic of Mali République du Mali (French) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968–1991 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Bamako | ||||||||

| Government | One-party military dictatorship | ||||||||

| Head of State | |||||||||

• 1968–1991 | Moussa Traoré | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1968–1969 | Yoro Diakité | ||||||||

• 1969–1986 | Post abolished | ||||||||

• 1986–1988 | Mamadou Dembelé | ||||||||

• 1988–1991 | Post abolished | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

• 1968–1971 | Yoro Diakité (First Vice President) | ||||||||

• 1968–1979 | Amadou Baba Diarra (Second Vice President) | ||||||||

• 1971–1991 | Vacant (First Vice President) | ||||||||

• 1979–1991 | Vacant (Second Vice President) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 19 November 1968 | |||||||||

| 26 March 1991 | |||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ML | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of Mali | ||||||||

On November 19, 1968, a group of young officers staged a bloodless coup and set up a 14-member Military Committee for National Liberation (CMLN), with Lt. Moussa Traoré as president.[16] The military leaders attempted to pursue economic reforms, but for several years faced debilitating internal political struggles and the disastrous Sahelian drought.[16][20]

A new constitution, approved in 1974, created a one-party state and was designed to move Mali toward civilian rule.[16][20] However, the military leaders remained in power.[20] In September 1976, a new political party was established, the Democratic Union of the Malian People (UDPM), based on the concept of democratic centralism.[20] Single-party presidential and legislative elections were held in June 1979, and Gen. Moussa Traoré received 99% of the votes.[16][20] His efforts at consolidating the single-party government were challenged in 1980 by student-led anti-government demonstrations that led to three coup attempts, which were brutally quashed.[16][20]

The political situation stabilized during 1981 and 1982 and remained generally calm throughout the 1980s.[20] In late December 1985, however, a border dispute between Mali and Burkina Faso over the mineral-rich Agacher strip erupted into a brief war.[21] The UDPM spread its structure to cercles and arrondissements across the land.[20]

Shifting its attention to Mali's economic difficulties, the government approved plans for some reforms of the state enterprise system and attempted to control public corruption.[16][20] It implemented cereal marketing liberalization,[22] created new incentives to private enterprise, and worked out a new structural adjustment agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[16][20] But the populace became increasingly dissatisfied with the austerity measures imposed by the IMF plan as well as their perception that the ruling elite was not subject to the same strictures.[16] In response to the growing demands for multiparty democracy then sweeping the continent, the Traoré regime did allow some limited political liberalization.[16] In National Assembly elections in June 1988, multiple UDPM candidates were permitted to contest each seat, and the regime organized nationwide conferences to consider how to implement democracy within the one-party framework.[16] Nevertheless, the regime refused to usher in a full-fledged democratic system.[16]

By 1990, cohesive opposition movements began to emerge, including the National Democratic Initiative Committee and the Alliance for Democracy in Mali (Alliance pour la Démocratie au Mali, ADEMA).[16] The increasingly turbulent political situation was complicated by the rise of ethnic violence in the north in mid-1990.[16] The return to Mali of large numbers of Tuareg who had migrated to Algeria and Libya during the prolonged drought increased tensions in the region between the nomadic Tuareg and the sedentary population.[16] Ostensibly fearing a Tuareg secessionist movement in the north, the Traoré regime imposed a state of emergency and harshly repressed Tuareg unrest.[16] Despite the signing of a peace accord in January 1991, unrest and periodic armed clashes continued.[16]

2000s

[edit]Konaré stepped down after his constitutionally mandated limit of two terms and did not run in the 2002 elections.[16] Touré then reemerged, this time as a civilian.[16] Running as an independent on a platform of national unity, Touré won the presidency in a runoff against the candidate of Adema, which had been divided by infighting and suffered from the creation of a spin-off party, the Rally for Mali. Touré had retained great popularity because of his role in the transitional government in 1991–92.[16] The 2002 election was a milestone, marking Mali's first successful transition from one democratically elected president to another, despite the persistence of electoral irregularities and low voter turnout.[16] In the 2002 legislative elections, no party gained a majority; Touré then appointed a politically inclusive government and pledged to tackle Mali's pressing social and economic development problems.[16]

2010s

[edit]In January 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) began an insurgency.[23] Rebel troops from the military appeared on state TV on 22 March 2012 announcing they had seized control of the country,[24] citing unrest over the president's handling of the conflict with the rebels. The former president was forced into hiding.

However, due to the 2012 insurgency in northern Mali, the military government controls only the southern third of the country, leaving the north of the country (known as Azawad) to MNLA rebels. The rebels control Timbuktu, 700 km from the capital.[25] In response, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) froze assets and imposed an embargo, leaving some with only days of fuel. Mali is dependent on fuel imports trucked overland from Senegal and Ivory Coast.[26]

As of July 17, 2012, the Tuareg rebels have since been pushed out by their allies, the Islamists, Ansar Dine, and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (A.Q.I.M.).[27] An extremist ministate in northern Mali is the unexpected result from the collapse of the earlier coup d'etat by the angry army officers.[27]

Refugees in the 92,000-person refugee camp at Mbera, Mauritania, describe the Islamists as "intent on imposing an Islam of lash and gun on Malian Muslims."[27] The Islamists in Timbuktu have destroyed about a half-dozen venerable above-ground tombs of revered holy men, proclaiming the tombs contrary to Shariah.[27] One refugee in the camp spoke of encountering Afghans, Pakistanis and Nigerians.[27]

Ramtane Lamamra, the African Union's peace and security commissioner, said the African Union has discussed sending a military force to reunify Mali and that negotiations with terrorists had been ruled out but negotiations with other armed factions is still open.[27]

On 10 December 2012 Prime Minister Cheick Modibo Diarra was arrested by soldiers and taken to a military base in Kati.[28] Hours later, the Prime Minister announced his resignation and the resignation of his government on national television.[29]

On 10 January 2013, Islamist forces captured the strategic town of Konna, located 600 km from the capital, from the Malian army.[30] The following day, the French military launched Opération Serval, intervening in the conflict.[31]

By 8 February, the Islamist-held territory had been re-taken by the Malian military, with help from the international coalition. Tuareg separatists have continued to fight the Islamists as well, although the MNLA has also been accused of carrying out attacks against the Malian military.[32]

A peace deal between the government and Tuareg rebels was signed on 18 June 2013.[33]

Presidential elections were held in Mali on 28 July 2013, with a second round run-off held on 11 August.[34] Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta defeated Soumaïla Cissé in the run-off to become the new President of Mali.[35]

The peace deal between the Tuareg rebels and the Malian government was broken in late November 2013 because of clashes in the northern city of Kidal.[36] A new ceasefire was agreed upon on 20 February 2015 between the Malian government and the northern rebels.[37]

In August 2018, President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita was re-elected for a new five-year term after winning the second round of the election against Soumaïla Cissé.[38]

2020s

[edit]Since 5 June 2020 street protests calling for the resignation of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta began in Bamako. On 18 August 2020 mutinying soldiers arrested President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta and Prime Minister Boubou Cissé. President Keïta resigned and left the country. The National Committee for the Salvation of the People led by Colonel Assimi Goïta took power, meaning the fourth coup happened since independence from France in 1960.[39] On 12 September 2020, the National Committee for the Salvation of the People agreed to an 18-month political transition to civilian rule.[40] Shortly after, Bah N'Daw was named interim president.[41]

On May 25, 2021, Colonel Assimi Goïta dismissed the transitional president Bah N'Daw and the transitional prime minister Moctar Ouane from their positions.[42] On 7 June 2021, Mali's military commander Assimi Goita was sworn into office as the new interim president.[43] According to Human Rights Watch (HRW) Malian troops and suspected Russian mercenaries from the Wagner group executed around 300 civilian men in central Mali in March 2022. France had withdrawn French troops from Mali in February 2022.[44]

In 2023, there was a proposal from Burkina Faso to establish a federation with Mali. The aim of the federation was to amplify the political and economic influence of both nations by combining their resources, territories, and populations. This initiative was part of a larger trend of African countries forming regional alliances to address shared challenges and advance their collective interests. The proposal faced criticism and opposition due to concerns over cultural, historical, and economic differences between the two countries, as well as issues regarding the distribution of power and resources and the potential loss of national sovereignty.[45]

See also

[edit]- Bamako history

- Timeline of Bamako

- History of Africa

- History of West Africa

- List of heads of government of Mali

- List of heads of state of Mali

- Politics of Mali

- History of Timbuktu

- Mali National Archives

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ouardia Oussedik: Les bifaces acheuléens de l’Erg Tihodaine (Sahara Central Algérien): analyse typométrique, in: Libyca 20 (1972) 153-161.

- ^ a b S. J. Armitage, N. A. Drake, S. Stokes, A. El-Hawat, M. J. Salem, K. White, P. Turner, S. J. McLaren: Multiple phases of North African humidity recorded in lacustrine sediments from the Fazzan Basin, Libyan Sahara, in: Quaternary Geochronology 2,1-4 (2007) 181–186.

- ^ a b Isla S. Castañeda et al.: Wet phases in the Sahara/Sahel region and human migration patterns in North Africa. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106,48 (2009) 20159–20163, doi:10.1073/pnas.0905771106.

- ^ Das Projekt Peuplement humain et paléoenvironnement en Afrique began in 1997 in Ounjougou (Pays dogon – Mali).

- ^ a b Stefan Kröpelin et al.: Climate-Driven Ecosystem Succession in the Sahara: The Past 6000 Years. In: Science, 320,5877 (2008) 765–768, doi:10.1126/science.1154913.

- ^ Arazi, Noemie. "Tracing History in Dia, in the Inland Niger Delta of Mali -Archaeology, Oral Traditions and Written Sources" (PDF). University College London. Institute of Archaeology.

- ^ Mcintosh, Susan Keech; Mcintosh, Roderick J. (Oct 1979). "Initial Perspectives on Prehistoric Subsistence in the Inland Niger Delta (Mail)". World Archaeology. 11 (2 Food and Nutrition): 227–243. doi:10.1080/00438243.1979.9979762. PMID 16470987.

- ^ McIntosh, Roderick J.; McIntosh, Susan Keech (2003). "Early urban configurations on the Middle Niger: Clustered cities and landscapes of power". In Smith, Monica L. (ed.). The Social Construction of Ancient Cities. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books. pp. 103–120. ISBN 9781588340986.

- ^ a b Mcintosh, Susan Keech; Mcintosh, Roderick J. (February 1980). "Jenne-Jeno: An Ancient African City". Archaeology. 33 (1): 8–14.

- ^ Shaw, Thurstan. The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns. Routledge, 1993, pp. 632.

- ^ al-Bakri in Nehemiah Levtzion and J. F. Pl Hopkins, eds and trans., Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History (New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1981, reprint edn Princeton, New Jersey,: Marcus Wiener, 2000), pp. 82-83.

- ^ ibn Khaldun in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds, and transl. Corpus, p. 333.

- ^ al-Idrisi in Levtzion and Hopkins, eds. and transl, Corpus, p. 108.

- ^ Stride, G. T; Ifeka, Caroline (1971). Peoples and empires of West Africa: West Africa in history, 1000–1800. Africana Pub. Corp. p. 49.

- ^ "The Empire of Mali, In Our Time – BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Country Profile: Mali". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. January 2005.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Country Profile: Mali". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. January 2005.

- ^ "Songhay". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2025-03-10.

- ^ John Middleton, ed. (1997). "Mali". Encyclopedia of Africa South of the Sahara. Vol. 3. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ "MALI GAINS PACT ON SOVEREIGNTY; Senegal-Sudan Federation Will Remain Closely Tied to France". The New York Times. April 1, 1960.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Background Note: Mali". Bureau of African Affairs, U.S. Department of State. February 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2005.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Background Note: Mali". Bureau of African Affairs, U.S. Department of State. February 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2005.

- ^ "Burkina Faso: A Small West African Country Struggles to Bring Peace to Mali".

- ^ Staatz, John M.; Dione, Josue; Nango Dembele, N. (1989). "Cereals Market Liberalization in Mali". World Development. 17 (5): 703–718. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(89)90069-7.

- ^ Mali clashes force 120 000 from homes. News24 (2012-02-22). Retrieved on: 23 Feb 2012.

- ^ Post-coup Mali hit with sanctions by African neighbours – Globe and Mail. Bbc.co.uk (2012-03-22). Retrieved on 2012-05-04.

- ^ BBC News – Mali Tuareg rebels control Timbuktu as troops flee. Bbc.co.uk (2012-04-02). Retrieved on 2012-05-04.

- ^ Post-coup Mali hit with sanctions by African neighbours. Theglobeandmail.com (2012-04-03). Retrieved on 2012-05-04.

- ^ a b c d e f Nossiter, Adam (July 18, 2012). "Jihadists' Fierce Justice Drives Thousands to Flee Mali". The New York Times.

- ^ "Mali's PM arrested by junta". Associated Press. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ "Mali PM resigns after being arrested by troops". Agence France-Presse. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ "Mali Islamists capture strategic town, residents flee". Reuters. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ "Mali – la France a mené une série de raids contre les islamistes". Le Monde. 12 January 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ "Five Malians killed in ambush blamed on Tuareg: army". AFP. 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ "Mali and Tuareg rebels sign peace deal". BBC News. 18 June 2013.

- ^ Mali sets date for presidential election Al Jazeera, 28 May 2013

- ^ "Ibrahim Boubacar Keita wins Mali presidential election". BBC News. 13 August 2013.

- ^ "Tuareg separatist group in Mali 'ends ceasefire'". BBC News. BBC. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ "Mali signs UN ceasefire to end conflict with northern rebels". BBC News. 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Incumbent President Keita wins re-election in Mali". France 24. 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Mali coup: Military agrees to 18-month transition government". BBC News. 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Mali: President Bah N'Daw decrees the dissolution of the CNSP". The Africa Report.com. 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Mali: Bah N'Daw sworn in as interim president". dw.com. Deutsche Welle. 25 September 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Mali's coup leader Assimi Goïta seizes power again". BBC News. 25 May 2021.

- ^ "Mali's military leader Goita sworn in as transitional president". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Mali troops and suspected Russian fighters accused of massacre". BBC News. 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Burkina urges 'federation' with Mali for joint clout". France 24. 2023-02-02. Retrieved 2023-02-03.